mrmmr mr mr' mr mr mr mr mr rm rm mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr rm mrmr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mr mm |

| Upcoming Expeditions |

||||

Technical Mountain

Notes

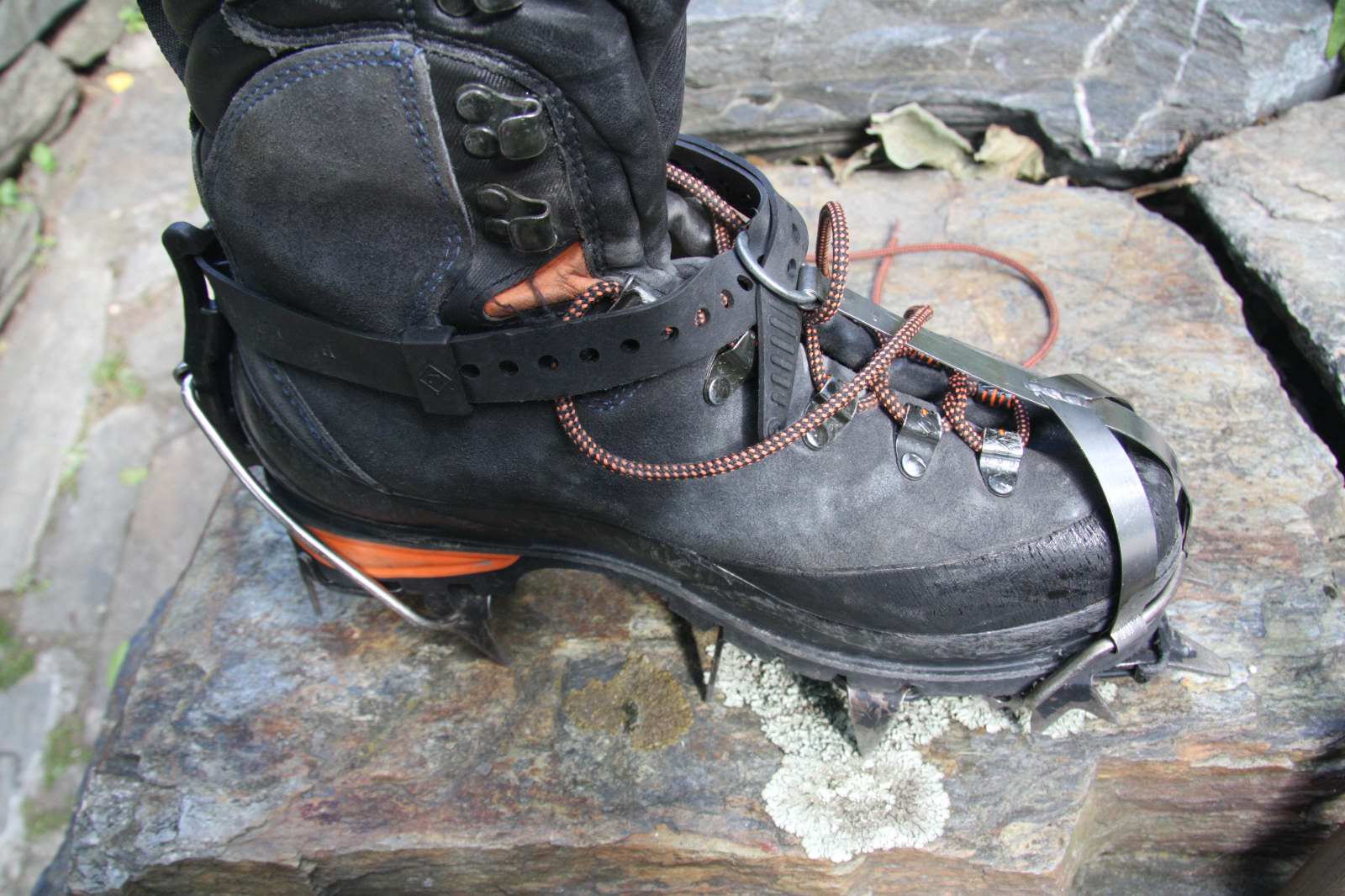

Modifying crampon bail straps for added security.

Crampon security to the boot is a vital component to ice and snow

climbing safety and many climbers have stories of detaching crampons

from a variety of attachments.

|

The security of "toe bail"

type crampons has has recently come to my attention following two fatal

accidents. The climbers involved happened to have "toe bail" crampon

attachments w/o an added stainless steel strap linking the toe bail to

the ankle safety strap. If the bail was to become detached then

the crampon would hang loosely on the safety strap. A steel strap adds

some stability to the attachment. I have added steel straps to some

bailed crampons along with additional diagonal straps to add stability.

The exercise was not cheap ($180) but neither is the experience of

discovering a crampon dangling from the ankle strap.

|

|

Snow and Ice Climbing

Time was pressing us now. We were very tired and

there was still no hint of an end. Looking down we could

see Ian using his knees. Mike rebuked him, saying that

even if he were bone-weary there was no excuse for such

bad technique when climbing. Ian looked up with a

mystified air. "Climbing? Who's climbing?" he

said. "I'm praying."

Phil Houghton NZ Alpine Journal, 1962.

Mountain climbing involves a direct

interaction with steep slopes and gravity, lifting arms

and legs and clawi ng skywards to the summit. The

descent, a downward plunge, comes as a relief, but thwart

with it's own pitfalls of fatigue and diminishing

technique. Snow and ice skills, using ice axe and

crampons, are best understood by seeing, doing and

feeling. Person al goals vary considerably, so your

learning experience, like climbing grades, should be open

ended. To become a master mountaineer requires commitment

to more than technique. Physical fitness, high

concentration, awareness of ability, fear control, and an

understanding of personal risk are all vital to be on the

inside, looking out! Accessing Routes

Heavy packs, fatigue, poor rock or snow conditions can

make access routes particularly hazardous. They are often

more dangerous than actual climbs: Loose moraine walls

are always hazardous. Snowgrass on steep slopes is very

slippery when wet. Soloing dictates caution on unstable

rock and wet snow. Access routes should be treated with

the same caution as serious climbs. The drive to and from

the road-head is no less serious.

Deep Snow Step Plugging:

When the legs plunge thigh deep into new snow and

progress grinds to a halt, consider the "double

step", amongst other grovelling options the

following: The Double Step - Step down with light

pressure until resistance is felt. Pause, then push

additional snow in from the side and apply full weight.

If the terrain is steep, an arrest axe position can be

used to distribute the load between hands and feet.

Power Step Plugging:

In a group of 3+ climbers, the leader step-plugs for a

minute or 20 paces at a faster than normal speed. They

then step one pace to the side and allow the next person

to lead before dropping to the tail-end. This allows each

person recovery time on a firm track while maintaining a

relative ly fast party travel speed. If roped in pairs,

the sequence can be modified to suit.

Self Arresting a Fall

A fall usually results from a foot slip or trip.

Self-Arresting should be practised often, but seldom

relied upon. It is an almost impossible manoeuvre to

perform on ice slopes or at speed. Mountaineers should

focus on preventing a slip with secure ice axe and

crampon technique. Accidents often happen when these

essential ice tools aren't being used.

Fall Run-outs: To reduce serious

consequences, taking route options with run-outs, rather

than cliffs or crevasses, allows a greater latitude for

error.

Arresting a Minor Slip: Climbers should practise

recovering from a stumble. A slip may be averted by

ramming a vertically held axe, sword-like into the snow,

while digging in the toe points. This is likely to be the

best opportunity to arrest a fall.

Arresting a Serious Slip: Various arrest

techniques are taught. Options should be practised.

Sequence: Try rolling into a feet downhill, flat on the

back position. Bring the axe up into a firm two handed,

across the chest, grip, then roll towards the head of the

ice-axe. Place your body in a strong triangular position

with your head and the axe pick at the apex. The feet,

wide apart, form a stable base. The body should be arched

off the snow with the feet apart and knees pressed into

the snow. Initially, keep your cramponed feet in the air

to avoid hooking. In wet snow you will need to dig them

into the snow to assist braking. Completing a self-arrest

will also ease the load on the belayer and their anchor.

Glissading

Boot sliding on sun softened snow with an erect body and

the leg support of the ice axe is called glissading. The

body is held in a flexed, erect position with hips

directly over the heels. Speed and direction control is

maintained by edging the boots. The glissade axe position

provides stability and arrest capability. On Sun softened

snow with a slope runout, controlled arcing turns can be

completed. If needed, a climber can roll into a

self-arrest without changing their handgrip.

The Ice Axe

The ice axe is the primary tool of the alpine climber. It

has four main components consisting of the pick, adze,

shaft and spike. The ice axe enables progress across

slopes with relative security. They evolved from the

large alpenstocks of 100 years ago. They are now

technical tools, used in conjunction with crampons. Most

axes have metal shafts with rubber sheath grips. The

optimum axe length is determined by the height of the

climber and inclination of climbs: The taller the

climber, the longer the axe; the steeper the climb, the

shorter the axe. Ice axe points should be kept sharp.

Sharpened adze corners are particularly useful for

cutting ice stances. A bevelled pick point & teeth

give better penetration & removal.

A general-purpose axe offers shaft and

pick support. They combine well with crampons to climb

moderately steep slopes. Most are about 70cms. long with

radius curved picks, a half set of teeth and a long shaft

spike for snow penetration.

A technical axe offers more security via

it's steeper radius or reverse curved pick and full set

of teeth. It's shorter shaft (50cms) swing combines well

with a similar ice tool on steep ice. Most technical

tools have interchangeable pick, adze & hammerhead.

North Wall Hammers add security and

hammering capacity. Most have reverse curved (positive

clearance) picks with 45cm shaft length. Curved handles

provide an easier wrist action for reaching over bulges.

They lessen knuckle damage on smooth ice, but inhibit

the vertical shaft use in snow. Most have modular picks

aiding easy replacement after breakage.

Crampons came into general use in the

1920's after a long debate over their ethics. They

improved climbing times, reduced step size and allowed a

for variety of boots. In 1938 two leading ice exponents

Vorg and Heckmair wore new 12 point crampons on the

ascent of the Nth. Face of the Eiger. H. Harrer and

Kasparek wore standard 10 point iceclaws. Step cutting

remained in use until toe points became universal on

crampons in the mid "60's. As an art, step cutting ,

the practised skill of the mountain guides, almost

disappeared. The development of curved pick ice-axes in

the late '60's complemented the toe-points. Crampons now

enable a mountaineer functional and fluid movement, with

the power and grace of a martial arts exponent.

Types: All high quality crampons are

adjustable in length. Most have 10 vertical points for

flat-footing. Longer vertical points work best in the soft

and sustrugi snows of the Southern Alps, Andes and the

Himalaya. The 2 toe (or front) points are where the most

variety lies. The toe points should protrude about 3cm in

front of the boot. Most have horizontally oriented,

curved toe points. These present more surface area and

resistance in soft snow. Most technical and waterfall ice

crampons have 1 or 2 vertical toe points for rigidity

and penetration. Broad, long heel points are also

important for New Zealand's soft snow conditions. Recent

crampon design improvements have been significant.

Attachment Systems

Ankle and toe straps have traditionally bound crampons to

boots. They continue use on soft, flexible boots. The toe

strap security is improved by a locking strap feed and

custom built toe-ankle connecting strap. Rigid crampons

with heel and toe clamps work best on stiff, new alpine

boots.